I found this during the week but didn't have time to post it on Friday. Perhaps it will lighten the mood after the somewhat heavy piece I published earlier.

This is from CNN a could of years ago, a weather man makes a fool of himself while suggesting, essentially, that climate scientists are bribed by the government to believe in anthropogenic global warming.

I like to think most people reading this could disabuse him of this belief without breaking a sweat.

Sunday 28 October 2012

The hidden cost: When we go to war, the environment suffers too.

Understandably it is the human cost of conflict that is the most immediate

and commonly thought of consequence of war. When governments decide to go to

war the damage to the environment that will be caused in a peripheral factor,

although history teaches that it is one that can often come back to haunt us

down the line.

It is just over a decade since the invasion of Afghanistan, a little less since the invasion of Iraq and enough time has now passed that the damage done to the planet by these conflicts can begin to be assessed. Last year the Eisenhower Study Group, based at Rhode Island's prestigious Brown University released the 'Costs of War' report, designed, in part, to do just that.

The report, based mainly on statistics for the US military alone, is not easy reading. 4.6 billion gallons of fuel is used every year by the American Department of Defense, with some military vehicles only averaging one mile to a gallon fuel economy. This alone constitutes a significant greenhouse gas source.

In Afghanistan there has been a 38% loss in forested areas since 1990, mostly due to illegal logging. With the chaos caused by the civil war of the 90s and the invasion of 2001 it has become impossible to regulate the logging industry. The resulting loss of habitats, reduction in soil quality and desertification may never fully be reversed. Deforestation has also been linked to an 85% reduction in migratory birds passing through Afghanistan.

The report also highlights the fur and skin trade in Afghanistan that has flourished since the 2001 invasion. Driven by soldiers and aid workings buying pelts as souvenirs the already minimal Snow Leopard population has been squeezed even further. While hunting of Snow Leopards is banned they are traditionally viewed as pests by rural communities and, as with logging, it is impossible to enforce the laws preventing their killing.

The report highlights a number of other factors, such as the poisoning of water sources by waste oil, the human health risks associated with the use of depleted uranium in tank shells and even the toxic particles thrown into the air by the burning of waste at military bases. For many it may make surprising reading but in reality it is something we should be aware of by now.

During the Vietnam War the use of the Agent Orange and other herbicides became one of the conflicts most lasting consequences. Over 40 million litres of Agent Orange was dropped on the Vietnamese jungle during the war, with 30 million litres of other similar chemicals adding to the deluge. Used in concentrations many times more potent than used in agriculture, the public health crisis this caused, with generations of Vietnamese children born disabled, hundreds of thousands estimated killed and American veterans suffering from increased rates of cancer, nerve damage and respiratory illness all due to exposure is one of the most haunting human consequences of the war. However environmentally it was also a catastrophe as Agent Orange did exactly what it was designed to do and destroyed at least 5 million acres of jungle and mangrove forest. Many of these areas are still bare, or have been replaced by invasive alien plant species, in both cases destroying rich and complicated ecosystems.

This then is the hidden cost of war, or rather the cost that gets pushed to one side by the inevitable human tragedy. Not just in Afghanistan, Iraq and Vietnam but at almost every site of modern conflict nature has been torn apart and often never recovered. Post-conflict this damage is also often overlooked, with efforts to repair the material and emotional damage of warfare taking precedence. There is very little to be done about this, but perhaps it could at least be acknowledged by those who lead us there that the cost of war isn’t just measured in lives and dollars.

It is just over a decade since the invasion of Afghanistan, a little less since the invasion of Iraq and enough time has now passed that the damage done to the planet by these conflicts can begin to be assessed. Last year the Eisenhower Study Group, based at Rhode Island's prestigious Brown University released the 'Costs of War' report, designed, in part, to do just that.

The report, based mainly on statistics for the US military alone, is not easy reading. 4.6 billion gallons of fuel is used every year by the American Department of Defense, with some military vehicles only averaging one mile to a gallon fuel economy. This alone constitutes a significant greenhouse gas source.

In Afghanistan there has been a 38% loss in forested areas since 1990, mostly due to illegal logging. With the chaos caused by the civil war of the 90s and the invasion of 2001 it has become impossible to regulate the logging industry. The resulting loss of habitats, reduction in soil quality and desertification may never fully be reversed. Deforestation has also been linked to an 85% reduction in migratory birds passing through Afghanistan.

The report also highlights the fur and skin trade in Afghanistan that has flourished since the 2001 invasion. Driven by soldiers and aid workings buying pelts as souvenirs the already minimal Snow Leopard population has been squeezed even further. While hunting of Snow Leopards is banned they are traditionally viewed as pests by rural communities and, as with logging, it is impossible to enforce the laws preventing their killing.

The report highlights a number of other factors, such as the poisoning of water sources by waste oil, the human health risks associated with the use of depleted uranium in tank shells and even the toxic particles thrown into the air by the burning of waste at military bases. For many it may make surprising reading but in reality it is something we should be aware of by now.

During the Vietnam War the use of the Agent Orange and other herbicides became one of the conflicts most lasting consequences. Over 40 million litres of Agent Orange was dropped on the Vietnamese jungle during the war, with 30 million litres of other similar chemicals adding to the deluge. Used in concentrations many times more potent than used in agriculture, the public health crisis this caused, with generations of Vietnamese children born disabled, hundreds of thousands estimated killed and American veterans suffering from increased rates of cancer, nerve damage and respiratory illness all due to exposure is one of the most haunting human consequences of the war. However environmentally it was also a catastrophe as Agent Orange did exactly what it was designed to do and destroyed at least 5 million acres of jungle and mangrove forest. Many of these areas are still bare, or have been replaced by invasive alien plant species, in both cases destroying rich and complicated ecosystems.

This then is the hidden cost of war, or rather the cost that gets pushed to one side by the inevitable human tragedy. Not just in Afghanistan, Iraq and Vietnam but at almost every site of modern conflict nature has been torn apart and often never recovered. Post-conflict this damage is also often overlooked, with efforts to repair the material and emotional damage of warfare taking precedence. There is very little to be done about this, but perhaps it could at least be acknowledged by those who lead us there that the cost of war isn’t just measured in lives and dollars.

Wednesday 24 October 2012

Why can't the world agree on the future?

This June the leaders of the world met in Rio to mark two decades since the

first 'Earth Summit'. They met to

talk about the environment, sustainability, clean energy, preserving the

natural wonders of the world and the green economy. Following the pattern of

climate and sustainability summits that the more cynical of us are now

programmed to expect there was a lot of talk but little action.

The task of getting the majority of the world's governments to agree, in the midst of a global financial crisis, on measures to tackle food, water and energy security for the poor while simultaneously taking steps to curb the damage done by industry to the climate was perhaps a tall order. However the Rio summit's failure is just one in a long line of 'once in a generation' meetings that have spectacularly failed.

Why?

Over the last few years, as with Rio and the Copenhagen climate summit before it, the state of the global economy has been the key limiting factor. Policies that are going to cost people in the short term, higher taxes on fuel for example, have become political suicide. US Presidential candidate Mitt Romeny summed this up perfectly when he stated in September ' I'm not in this race to slow the rise of the oceans or to heal the planet…my promise is to help you and your family'. Faced with austerity public opinion, and by extension the opinion of policy makers, has swung out of favour with saving the whale…

But what about before the credit crunch?

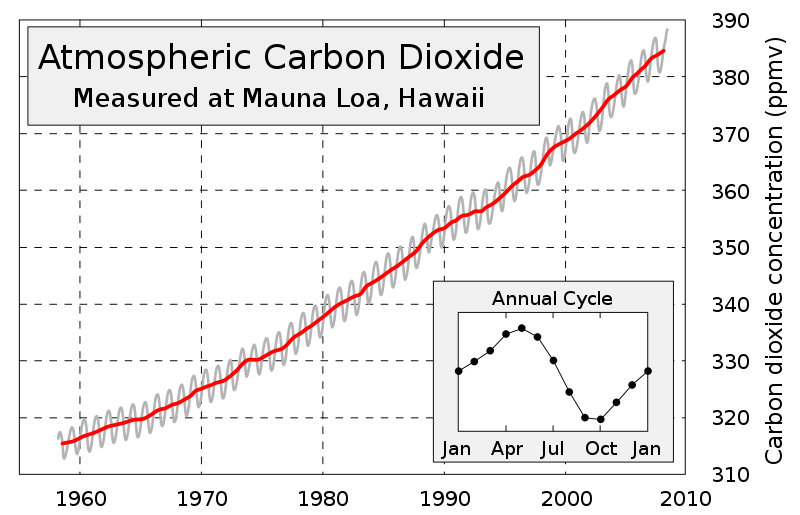

In 1997 the world (with the exception of America and Australia) signed the Kyoto Protocol. In what is still one of the milestones of the environmental movement it was agreed to reduce emissions of Carbon Dioxide, Methane, Nitrous Oxide and Sulfur Hexafluoride by at least 5.2% before 2012. As anyone with even a vague knowledge of climate science will tell you, this goal was catastrophically missed. Today emissions of Carbon Dioxide alone are at an average of 387ppm, with them predicted to rise to 400ppm by 2016. As the graph below shows when the Kyoto Protocol was signed in the late nineties it was around 360ppm.

The reasons for the failure of Kyoto are, in general, the same reasons for the failure of almost every other similar agreement. The inability to get the America to sign up in full to cuts in emissions that will effect both the US auto and petroleum industries has been cited as the driving force in the continual rise in greenhouse gas emissions. The truth is that while the US is one of the world’s greatest polluters and its lack of action is a significant factor, the lack of mechanisms to enforce supposedly binding agreements on emission reductions has left Kyoto and similar accords toothless. By the estimation of the UN China became the world's largest single polluter in 2008, when it emitted over 7 billion metric tonnes of Carbon Dioxide. It did this despite having signed up (and still being signed up) to the Kyoto Protocol.

Technology, or the lack of it, has certainly played a part as well. The growth of the renewable energy sector has, to date, not kept pace with demand. The burning of fossil fuels is still the most efficient and cost effective way of generating power. Apart from countries with natural reserves of geothermal energy such as Iceland it is still practically implausible for an economy to be built around renewables.

The expectations of people, especially in the developing world, is also relevant. We have grown to expect a quality of life that requires everything from cheap air travel to washing machines in our homes. As long as we continue to want this, and as long as people aspire to it, cutting our pollution of the Earth will be problematic at best. There seems to be no easy solution to this, for unless we give up our own privileges how can we expect others not to aspire to them?

The example presented above is climate-centric but the same factors could be applied to many others issues. The global community has so far been ineffectual in stopping the illegal logging that is tearing apart rainforest ecosystems or making sure that food and development aid is used where it is needed and not siphoned off into the purses of corrupt officials. However it is with climate change that the reasons for our inability to agree and act are most palpable. We’ve come a long way since the optimism of Rio 1992, and we haven’t been moving in the right direction.

The task of getting the majority of the world's governments to agree, in the midst of a global financial crisis, on measures to tackle food, water and energy security for the poor while simultaneously taking steps to curb the damage done by industry to the climate was perhaps a tall order. However the Rio summit's failure is just one in a long line of 'once in a generation' meetings that have spectacularly failed.

Why?

Over the last few years, as with Rio and the Copenhagen climate summit before it, the state of the global economy has been the key limiting factor. Policies that are going to cost people in the short term, higher taxes on fuel for example, have become political suicide. US Presidential candidate Mitt Romeny summed this up perfectly when he stated in September ' I'm not in this race to slow the rise of the oceans or to heal the planet…my promise is to help you and your family'. Faced with austerity public opinion, and by extension the opinion of policy makers, has swung out of favour with saving the whale…

But what about before the credit crunch?

In 1997 the world (with the exception of America and Australia) signed the Kyoto Protocol. In what is still one of the milestones of the environmental movement it was agreed to reduce emissions of Carbon Dioxide, Methane, Nitrous Oxide and Sulfur Hexafluoride by at least 5.2% before 2012. As anyone with even a vague knowledge of climate science will tell you, this goal was catastrophically missed. Today emissions of Carbon Dioxide alone are at an average of 387ppm, with them predicted to rise to 400ppm by 2016. As the graph below shows when the Kyoto Protocol was signed in the late nineties it was around 360ppm.

The reasons for the failure of Kyoto are, in general, the same reasons for the failure of almost every other similar agreement. The inability to get the America to sign up in full to cuts in emissions that will effect both the US auto and petroleum industries has been cited as the driving force in the continual rise in greenhouse gas emissions. The truth is that while the US is one of the world’s greatest polluters and its lack of action is a significant factor, the lack of mechanisms to enforce supposedly binding agreements on emission reductions has left Kyoto and similar accords toothless. By the estimation of the UN China became the world's largest single polluter in 2008, when it emitted over 7 billion metric tonnes of Carbon Dioxide. It did this despite having signed up (and still being signed up) to the Kyoto Protocol.

Technology, or the lack of it, has certainly played a part as well. The growth of the renewable energy sector has, to date, not kept pace with demand. The burning of fossil fuels is still the most efficient and cost effective way of generating power. Apart from countries with natural reserves of geothermal energy such as Iceland it is still practically implausible for an economy to be built around renewables.

The expectations of people, especially in the developing world, is also relevant. We have grown to expect a quality of life that requires everything from cheap air travel to washing machines in our homes. As long as we continue to want this, and as long as people aspire to it, cutting our pollution of the Earth will be problematic at best. There seems to be no easy solution to this, for unless we give up our own privileges how can we expect others not to aspire to them?

The example presented above is climate-centric but the same factors could be applied to many others issues. The global community has so far been ineffectual in stopping the illegal logging that is tearing apart rainforest ecosystems or making sure that food and development aid is used where it is needed and not siphoned off into the purses of corrupt officials. However it is with climate change that the reasons for our inability to agree and act are most palpable. We’ve come a long way since the optimism of Rio 1992, and we haven’t been moving in the right direction.

Friday 19 October 2012

Fun things on a Friday.

To break up the serious here is an entertaining video I found a while back. Professor Katey Anthony from the University of Alaska explains a way in which methane can build up in arctic lakes and is subsequently trapped under the ice covering the water.

She then goes to show an commendable disregard for health a safety by setting the stuff on fire...

Enjoy.

She then goes to show an commendable disregard for health a safety by setting the stuff on fire...

Enjoy.

Monday 15 October 2012

In the begining...

Rather than dive straight in at the deep end it is best,

when considering how we’re changing the planet, to start at the beginning and

ask ‘What have we done so far?’. To

do this it is becoming increasingly popular to view the period in which humans

have significantly changed the Earth as the Anthropocene.

First proposed in the early 2000s the notion of a new period of geological

time has often been controversial; some such a William Ruddiman have suggested

that humans began altering the Earth over 8,000 years ago (Ruddiman, 2003). A

more commonly held view is that it is since the 1800s that we have, driven by

the march of industrialisation, truly begun to change the Earth. In 2011 the Anthropocene was very well

summarised by Steffen et al in the

Philosopical Transactions of The Royal Society. I will briefly review this

paper in order to sum up the key concepts of the Anthropocene.

The first thing to note is that the concept of humans

altering the planet is not a new one. Steffen et al point out that since the late 1800s the effect of human

actions on the Earth has been documented, in particular the paper cites

Stoppani’s The Earth as Modified by Human

Action of 1864. What is clear though is that it is only much more recently

that the term Anthropocene was coined, Steffen et al attribute the first use of the it to Eugene Stoermer in the

1980s although when the concept of the Anthropocene was first fully defined is

more vague. Some attribute this definition to Paul Cruzten, a co-author of this

paper (The Economist, 2011).

Steffen et al firmly

reject the ‘early-Anthropocene’ hypothesis as suggested by Ruddiman. It is

acknowledged that human activity has effected natural ecosystems as far back as

‘pre-history’, but to quote directly from the paper early humans were ‘never able to fully transform the ecosystems

around them. They certainly could not modify the chemical composition of the

atmosphere or the oceans at the global level; that remarkable development would

have to wait until the advent of the Industrial Revolution a few centuries

ago’. As this quote suggests the idea that even pre-industrial human

activity such as early fossil fuel use, forest clearance 8,000 years ago or the

development of rice cultivation 5,000 years ago, both events at the centre of the

‘early-Anthropocene’ hypothesis (Ruddiman, 2003) had a significant effect on

the Earth on a global scale is also denied by Steffen et al.

Like others Steffen et

al chose to place the Anthropocene as beginning with the Industrial

Revolution, around the year 1800 (although as is noted, there is no definitive

‘start’ but a transition from agricultural to industrial between 1750 and

1850). Driven by the large scale exploitation of fossil fuels and the ability

to synthesise nitrogen for use as a fertiliser humanity ‘shattered the energy bottleneck’ that had previously contained both

population and activity. Fossil fuel use sky rocketed, coupled with land use

changes and massive releases of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere. By 1850

when the industrial revolution was spreading from England to the rest of the

world humans had finally managed to ‘modify

the chemical composition of the atmosphere or the oceans at the global level’.

Steffen et al use a number of

indicators to track anthropogenic changes to the world’s ecosystems from 1800

onwards. CO2 concentrations in the atmosphere are perhaps the most

direct, showing an increase from 277 to 296ppm in the 150 years following 1750.

However other variables such as urban population, biodiversity loss, water use

and fertiliser consumption (among others) can all be used to track the growing

activity of mankind and its consequences. Analysis of this data leads Steffen et al to the conclusion that after the

Second World War there began a period known as the Great Acceleration. The data in the paper shows that, driven by

post-war technological advances and greater global cooperation in matters of

trade and economic recovery (itself driven by the Bretton Woods accord) almost

every indicator of human development rose exponentially, mirrored by a rise in

the level to which the Earth system was effected by human activity.

As is highlighted in section six of the paper, the nature of

the Anthropocene is now changing. The Great

Acceleration is over, although many of the trends that defined it continue.

What is coming next is conjecture. As Steffen et al observe resource constraints upon fossil fuels will almost

certainly start to check economic growth in the years to come, especially in

the burgeoning, oil and coal dependant economies of Asia. Alongside this the

environmental movement that has grown over the last few decades is now a

serious player in global politics, although getting countries to agree on

emissions reductions in order to curb climate change still proves a difficult task. How effective we are in reducing our

emissions of greenhouse gases in the next few years may well define the nature

of the Anthropocene in the future. It could well be that we enter a third stage

of the Anthropocene, defined by massive changes to the environment around us.

The purpose of this review is however not to delve into the

future of the Anthropocene, that will come in later weeks. Steffen et al have in this paper summed up the

trends within the Anthropocene so far very well and I have tried to highlight

the most important of these trends above. While calling the Anthropocene a new

geological time period may be a step too far it is clear from this paper that

in the context of understanding current climate change the concept of the

Anthropocene is key.

(The paper itself can be found here http://biospherology.com/PDF/Phil_Trans_R_Soc_A_2011_Steffen.pdf)

References:

- · Nb. All quotes and figures not references individually in the text above are drawn from The Anthropocene: conceptual and historical perspectives. Will Steffen, Jacques Grinevald, Paul Crutzen and John McNeil. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. 2011 369. 842-867.

- · The anthropogenic greenhouse era began thousands of years ago; Ruddiman. Climatic Change 61: 261–293, 2003.

- · The Economist, May 2011. http://www.economist.com/node/18741749

Friday 12 October 2012

The people who run the world

In the face of the huge and wide ranging changes we as a

species are forcing upon the planet you might be forgiven for wondering what

one person can do. Can a single man or woman do anything to alter the course we

have collectively set for the world? Probably not. Certainly as a private

citizen there is no direct action that you or I can take as an individual to

stop what is going on around us. By all means turn off your lights and recycle

your takeaway packaging but, as the more cynical among us often point out, it

will only make a real difference if everyone does the same.

However there are some people who can do more than most.

From Washington to Whitehall, Berlin to Beijing those who govern have, more

than anyone else, the power to control how we shape the future of the planet.

There are Presidents and Prime Minister (who you’ve probably heard of), cabinet

ministers (who you might have heard of) and special advisors (who you won’t

have heard of). All of them are, in one way or another, responsible for the policy

that governs what we can and can’t do to the planet.

This blog aims, in the beginning at least, to shine a light

on the decisions that these people have made (and continue to make). From

funding for renewables to arctic drilling rights it is important that we know

what decisions are being made on our behalf and how they will change our world.

We must also ask how we as a wider society are contributing to the

anthropogenic changes to the Earth. Is it the energy companies and

multinationals than need to change their ways or do we all need to look in the

mirror first?

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)